Dr. Ali Moussa Iye

Ladies and Gentlemen,

As we are celebrating the launch of the International Decade for People of African Descent (2015-2024), it is worth recalling the three kind of denials that Africans and people of African descent had to overcome over the last four centuries:

- Denial of their humanity and dignity through the numerous attempts to bestialize them and transform them into the others’ designs

- Denial of their history and culture by rejecting them in the wildness of nature in the world of animals,

- Denial of their rights and citizenship through all types of policies and strategies of racism and discrimination .

Most of the prejudices against people of African descent are rooted in the belief – which still continues – , that they have not created any significant civilization, and that they made any valuable contribution to the progress of humanity.

Every sign of civilization found in Africa was generally attributed to outsiders coming from other regions. The Ancient Egyptian civilization is not the only case where Africa is denied ownership of its history and heritage. We can speak of the Ethiopian civilization. We can speak of the North Africa Civilizations.

These prejudices are not only the result of ignorance, they are part of ideological constructions which aim at justifying the slave trade, slavery, colonization, segregation and Apartheid since the 16th century.

They were rigorously elaborated by the most eminent thinkers and scientists that Europe and America have produced. These prejudices have nourished what is today called the “Big Colonial Library” which offers to the general public millions of writings, images and illustrations expressing the supremacy of European “race” and civilization. And the inferiority of the black race.

In fact, all means of intelligence, intellectual, scientific, religious and legal resources, were used to make acceptable this massive violation of basis values of humanity .

These prejudices and their consequences of inequality and discrimination have survived the abolition of slavery and the formal end of colonization. These are still vehicled by the media, cinema, television, textbooks and by politicians. They continue to influence the ways people of African descent are perceived and question their capability to master their life. It is such ideology which is the root cause of many hate speeches and crimes, such as the one that recently took the life of nine innocent African-American citizens in a church in Charleston in the USA.

These constructed discourses have built a wall of silence around the slave trade and slavery across the world, to cover the legacy of slavery, and its transition to colonialism and Apartheid. This “silence” is an attempt to escape responsibility and reflection on the inhumanity of the predatory economic and socio-political system that shaped our modern world and – unfortunately – continues to serve as model of development. This silence is not only a reflect of a hidden guiltiness, it is also the expression of an even more intolerable sentiment of indifference towards undifferentiated anonymous victims whose life is considered less valuable.

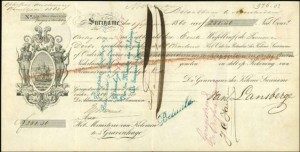

It is instructive recalling that slavery was the only crime against humanity for which the perpetrators (not the victims) were financially compensated for the lost their human properties in the process of abolition and not the victims. This only fact illustrates the ethical and moral disaster on which the modern world was built. It remains indeed very difficult to understand how a tragedy of this scale could be ignored and silenced for so long. What kind of resources have been mobilised to achieve such result?

It is instructive recalling that slavery was the only crime against humanity for which the perpetrators (not the victims) were financially compensated for the lost their human properties in the process of abolition and not the victims. This only fact illustrates the ethical and moral disaster on which the modern world was built. It remains indeed very difficult to understand how a tragedy of this scale could be ignored and silenced for so long. What kind of resources have been mobilised to achieve such result?

Ladies and gentlemen,

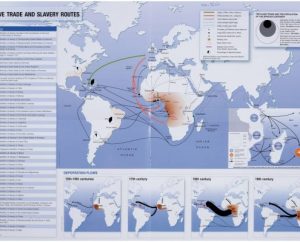

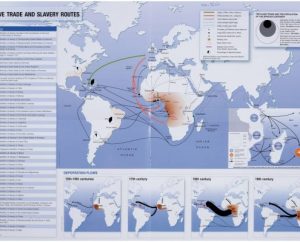

Allow me to recall some facts. Historians estimate that a total of around 30 to 40 million Africans were deported from the different regions of Africa and enslaved in Europe, in the Americas and Caribbean, in Asia, in the Indian Ocean and in the Middle East. If we add the number of those who died during the capture, the rebellions, the walk towards ports, the concentration camps and the “Middle Passage”, there were hundreds of millions of lives that were taken from Africa.

As an example of the devastation of this continent, whose population seriously declined for at least 4 centuries, demographists tell us that without the slave trade the total number of Africans in the end of 19th century should have reached 200 million rather than the estimated 100 million. You can imagine what would have been the population of Africa today without this “maafa”, the Great Catastrophe in Swahili.

The slave trade and slavery paved the way to renewed forms of slavery which still affected millions of peoples, in particular women and children in different parts of the world. This tragedy is at the foundation of our modern world.

Why? And how? Through the capital accumulated during the trade which contributed to the industrialization and enrichment of Europe and America, through the common heritages which are the main sources of today’s artistic creations, and through the combat against slavery which has profoundly influenced Human Rights’ movements, this history has participated in the emergence of modernity.

What lessons can societies, which have practiced such collective crimes, draw from this history? What could we expect from a “civilization” that passed through this kind of inhumanity? How to appreciate “humanistic values” that were introduced at the height of the slave trade and slavery? These are ethical and philosophical questions that are not, in my view, sufficiently asked in the academic and political discourses.

Indeed, various explanations are advanced by scholars in order to understand this silence.

Unlike other tragedies, for which the perpetrators could be identified as distinct from the rest of the nation (f.i. nazism), the slave trade involved a very wide range of public and private players, whose participation over several generations was entirely legal. Slave trade affected important sectors in the economic life of the countries that profited from it, including commerce, shipbuilding, mining, manufacturing, agriculture, banks and insurance.

This diffusion or dilution of responsibility within societies has delayed the recognition of the crime. The enshrining of such criminal practice in law, notably through the monstrous Black Codes, also facilitated denial of responsibility. Fulfilment of the “duty to remember” was also rendered more difficult by the persistence of its serious consequences in the form of the racial prejudice and discrimination, from which the descendants of slaves have suffered, to the present day.

In some countries involved in the slave trade and slavery, there have been attempts to sidestep the issue, by focusing on the abolition laws and the struggle of the abolitionists, while neglecting to recall the horrors of the system, its legacy and the furious resistance of the enslaved peoples themselves for their dignity and liberation.

It is overlooked that – before being kidnapped and put into bondage – enslaved Africans were free men and free women possessing their own culture, knowledge and history. Far from being simply a victimized subject, resigned with their conditions, as is often depicted in the colonial literature, they resisted the dehumanizing conditions in which they were forced to live. From the moment their villages were attacked, throughout their forced walks to the ports, throughout their martyrdom in the concentration camps, throughout the “voyages of no return”, behind the caravans or in the slave ships, and throughout the forced labour in households, in plantations and mines, enslaved Africans revolted and used every means at their disposal, including collective suicide, to escape the condition of slavery.

But the most profound resistance, the most radical of all was their cultural resistance. The enslaved Africans used what is considered as the essence of humanness, the culture, to combat their subjugation. Because of the blind and ignorant belief in their own racial superiority, the slave owners were incapable of understanding or anticipating the potential of slaves to use their culture as a resource of resistance.

It was in the spiritual and artistic fields, the most fertile seedbed of life forces, that this resistance found its most lasting expression. The force of their cultures not only helped them to survive the dehumanisation process of slavery, but also to influence and – in a certain way – “re-humanise” slave societies.

In some parts of the world this resistance transformed itself into huge social movements and even into a revolution. This was the case with the movement commonly known as the Zanj rebellions, which occurred in Iraq between 6th to 9th Century. From 869 to 883, thousands of African Slaves from the Horn of Africa working in the salt marshes in Southern Iraq joined forces with other groups to revolt against their exploitation and claim social change. The Zanj rebels won the war, even established their state with its own capital called Moktara and seriously threatened and challenged the reign of the Abbasid Caliphate during 14 years. The economic, political and social consequences of this revolt profoundly affected the whole Islamic world. It is during this period that in the Arabic world theories of racism against black people have been written in their books.

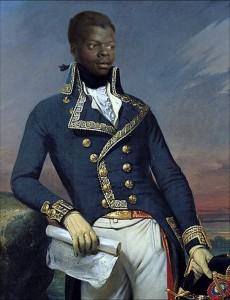

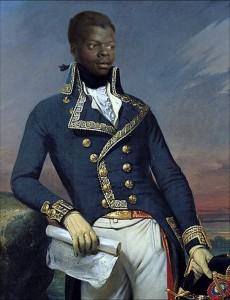

Another resistance of enslaved African that is worthy to mention, is the Haitian rebellion in the Caribbean region. On the nights of 22 to 23 August 1791 an insurrection of slaves broke out on the Island of Saint Domingue and under the leadership of Toussaint Louverture and others evolved to be a revolution, which led to the independence of Haiti in 1804. It was the first victory of enslaved peoples which overthrew their oppressors in human history,.The Haitian revolution is considered as the first revolution to put in real practice the universality of human rights that French and American revolutions failed to do by perpetuating the slave trade and slavery system. This revolution brought by slaves had a considerable impact on the emancipation movements that were to lead to the independence of peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (f.e. Simon Bolivar).

Another resistance of enslaved African that is worthy to mention, is the Haitian rebellion in the Caribbean region. On the nights of 22 to 23 August 1791 an insurrection of slaves broke out on the Island of Saint Domingue and under the leadership of Toussaint Louverture and others evolved to be a revolution, which led to the independence of Haiti in 1804. It was the first victory of enslaved peoples which overthrew their oppressors in human history,.The Haitian revolution is considered as the first revolution to put in real practice the universality of human rights that French and American revolutions failed to do by perpetuating the slave trade and slavery system. This revolution brought by slaves had a considerable impact on the emancipation movements that were to lead to the independence of peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean (f.e. Simon Bolivar).

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is to break this heavy silence that the Slave Route Project was created by UNESCO in 1994. Because ignoring such a major tragic historical event constitutes in itself a denial of human dignity and an obstacle to peace, mutual understanding, reconciliation and cooperation among nations. The Project is the result of the heated debate that rose when European countries decided in 1992 to celebrate what they called the 500th Anniversary of the Encounters of the Two Worlds. The date corresponded to the so called “Discovery of the New World”. Natives and Afro descent peoples in the Latin America and Caribbean strongly opposed to such slogan to designate a painful event from their perpective. They stressed that the so called Discovery of America resulted with two of the greatest genocides in human history: the extermination of the indigenous peoples of the Americas and Caribbean and the enslavement of African peoples.

It is in response to the controversy raised by this celebration and to contribute to mutual understanding that two programmes were created by UNESCO in early 1990’s: the programmes on indigenous people and the Slave Route project From its inception, the ethical, political and cultural stakes behind the UNESCO Slave Route Project were clearly stated.

Before being an object of research, the slave trade and slavery should be first be posed as an ethical and moral question. Because what is at stake, is the barbarity that societies are capable of unleashing, especially those societies claiming the privilege of the civilisation. It is the contradiction between the moral aspirations of peoples and their subjugation to inhuman economic systems of their society which needs to be addressed. If today the principles of the universality and indivisibility of Human rights seem to be largely accepted, it is important to understand the sin which is at the origin of the human rights movements. The sin is therefore the double standard of human rights. The sin is, on the one hand we speak of the human rights standard that everybody is born free, and the perpetuation of slavery and slave trade at the exact moment that this new humanistic value is being promoted.

It is important to bear in mind this history, in order to challenge the current dangerous discourses on “the clash of civilisations and religions” and the “war against terror” which risk to lead us to a new ethnocentric vision of human rights and a new division of human kind.

The comprehension of this silenced chapter of the world history makes it possible to better grasp the genealogy binding the slave trade to other historic crimes, such as the extermination of Natives in the Americas, the Shoa, the apartheid and more recent genocides. Because it is the same logic that is behind these genocides.

The situation of Africa today cannot be understood without reference to this systematic human, intellectual and cultural haemorrhaging to which the continent was subjected over centuries of trans-Saharan, trans Indian Ocean and transatlantic slave trading. We cannot understand the exclusion and poverty experienced by black populations in the Americas, the Caribbean, in Europe, in the Indian Ocean and elsewhere, without explaining the system of exploitation and inequality inherited from slavery which has persisted long after the abolitions and decolonisation. This tragedy concerns the whole humanity and calls out to all of us whatever our origin, because of the universal silence that has surrounded it, the troubling light it sheds on the discourse used to justify it, and psychological scars it left in our heads. In the heads of descendants of slavery victims and in the heads of descendants of slave owners.

Far from being an event of the past, this tragedy engages us because it raises some of today’s burning issues of our multi-ethnic post-slavery societies: the fight against racial prejudices and discrimination, the equitable share of power and resources, national reconciliation, cultural pluralism, construction of new identities and citizenships for better living together, fight against economic immorality and new forms of servitude.

From the beginning, the Slave Route project raised strong interest in various countries, despite the limited resources at its disposal. It favoured the launching of awareness-raising campaigns, the increase of research, the production of various material and the mobilisation and empowerment of marginalized populations. It made significant accomplishments in 20 years.

Six reasons may explain this success:

- From the beginning UNESCO has clearly posed the ethical and political stakes of the Project .It helped different stakeholders to understand that the remembrance of the slave trade is not intended to resurface a painful and traumatic past with the aim of producing guilt, but instead it is intended to build a common heritage that could facilitate a better understanding of today’s world and perhaps better prepare the future of our multi-ethnic

- By placing the issue of slave trade and slavery at a global level and by imposing it as an international issue, the Project contributed to “de-racialize” this tragedy and present it as a tragedy of the whole humanity.

- The project began its activities with a scientific approach to take the necessary distance and transcend the emotion raised by such painful subject. Its succeeded to reconcile the exigencies of the scientific research and the duty to remember.

- The Project privileged the entry point of culture by emphasising on the cultural interactions and shared heritage of the tragedy (f.i. jazz, rap).

- The project developed a holistic vision of the question by tackling its different dimension: education; common heritage, preservation of written archives and oral traditions, inventory of sites of memory, promotion of the living cultural expressions, the contributions of African Diaspora to modern societies

- The Project addressed critical issues which contribute to current societal debates: identity crisis, living together, new forms of citizenship etc

- The Project extends its activities in regions and countries where the issue remain taboo in order to break the silence (Middle East, Indian Ocean, Red Sea, And in America )

One of the main achievements of the Slave Route Project was to have substantially contributed to the recognition of the Slave trade and slavery as a “crime against humanity” at the Durban World Conference against Racism in 2001. As you all know, this Conference was a crucial historical moment for all those who were fighting against the silence over the slave trade and against the falsification of history. The recognition of slavery as a crime against humanity opened new perspectives for the struggle of people of African descent for their rights.

Another important contribution was the erection in 2014 of a Memorial at the United Nations in New York, a memorial dedicated the victims of the slave trade and slavery. The design that won the international competition that we organised is called “ the Arch of Return” by the a famous American architect from Haitian origin. The construction of this Memorial at the UN is a strong symbol of global remembrance which marks the recognition of this tragedy as a tragedy of the whole humanity.

Another important contribution was the erection in 2014 of a Memorial at the United Nations in New York, a memorial dedicated the victims of the slave trade and slavery. The design that won the international competition that we organised is called “ the Arch of Return” by the a famous American architect from Haitian origin. The construction of this Memorial at the UN is a strong symbol of global remembrance which marks the recognition of this tragedy as a tragedy of the whole humanity.

Finally, the Slave Route project actively participated in the discussions and debates which ended up with the proclamation by the United nations of an International Decade for people of African descent (2015-2024) and the adoption of a Programme of activities articulated around the theme of Recognition, Justice and Development. The ownership and success of this Decade will depend not only on the actions of governments and their public authorities but also of the mobilisation of the civil society organisations, scholars, artists and journalists, educators and all citizens of good will engaged in the fight against the legacy of the slave trade, slavery and colonisation. This Decade offers to all of us and in particular to governments and local authorities an opportunity to engage concrete activities in different areas in order to accomplish their “duty to remember”. Please note that due to human rights developments there is also a “right to remember”.

In a country like Nederland, which played a crucial role in this tragic history, the following activities may be envisaged:

- Development and reinforcement of research at universities and academic institutions to address specific issues

- Translation of available research into pedagogic materials to be used by schools

- Production and broadcast of special TV and radio programmes on the heritage and legacy of the slave trade and slavery

- Inventory, preservation and promotion of important sites of memory related to this history in the country to used as tools for education

- Initiation of a series of lectures on the consequences of this history and the conditions for a genuine reconciliation and new living together

The Slave Route project is committed to share its experience and expertise in order to participate in this collective effort to pacify and reconcile our societies.

I thank you for your attention.